Editor's note:

During the 2020 'lockdown', I took part in the viral challenge that required Facebook users to share 'an influential album a day' (no words allowed!). Having previously completed that challenge the year before, I decided to take a slightly different approach second time around and explain why those albums are important to me. As such, these musings form a sort of self-indulgent 'musical biography' which seems in keeping with some of themes of this blog, hence this one-off post. Should you wish to indulge yourself further there is an accompanying Spotify playlist.

(1) 'Van Halen' by Van Halen (1978)

It started with guitars. Big guitars. The glorious riff to Dire Straits ‘Money for Nothing’ was the soundtrack of the Summer of ’85 and a definite beginning for me. A TDK cassette copy of Iron Maiden’s ‘Number of the beast’ soon followed from someone, somewhere. The following spring, I bought the cassette of Van Halen’s ‘5150’ from What Records in Coalville. Even though this was Van Halen mk 2 (the more pop-oriented Sammy Hagar era), I knew enough about rock music by then to know that Eddie Van Halen was a revered guitar player. And it was guitars I was interested in. The album had only been out about a month but it had already been marked down to £3.99 – Coalville’s favoured brand of metal was of the heavy and British variety. My cassette of 5150 was passed around most of my peers at school for the next year. When it was returned to me sans inlay, I shamefully ‘acquired’ a replacement inlay from St Martin’s Records in Leicester, spurred on by a more daring friend...

I’d found ‘my band’, and, by the end of that summer, I’d found myself: I’d devoted my pocket and paper round money to acquiring their entire back catalogue; I’d filled my school ‘rough book’ with dozens of VH logos, and grown a pretty good mullet.

I can’t imagine what it must have been like to hear this, the self-titled Van Halen debut in 1978. ‘Imagine Jagger and Hendrix in the same band and you’re halfway there’ is how the ‘recommended recording’ review of (my former employer) Andy’s Records put it (I wish I’d written that one). The Guardian columnist Michael Hann, a few years ago, wrote a very controversial article, arguing that, after the Beatles, Van Halen were the most influential rock band of all time. So controversial that The Guardian have pulled it from their online archive but you can read it here. https://thequietus.com/articles/23095-van-halen-the-band-the-velvet-underground-could-only-dream-of-being

I probably wouldn’t go that far, but, undoubtedly, ‘Eruption’ changed guitar playing forever, for better or worse, inspiring a million pale imitations, and ‘hair metal’ if you believe some.

And for me, at the time, it was all about Eddie Van Halen. I’m wondering, if in some roundabout way, his playing wasn’t my first gateway to jazz. No-one would argue that Eddie is an out and out jazz player, although he often cited Allan Holdsworth as a big influence. Let's remember too that the Van Halens' father, Jan, was a professional jazz musician - they even recorded this trad jazz tune with him on their 1982 album ‘Diver Down’.

Critics would sometimes argue that Eddie’s playing was noodly, self-indulgent, flashy – but aren’t most jazzers that? He also had that looseness and swing. And the tone on those early albums! (‘The brown sound’!). Yet, even in his most ‘out there’ moments, Ed always brought it back to the melody, serving the song. And his rhythm playing was totally underrated (and equally unique) – as evidenced by Ain’t Talkin’ Bout Love and most of this raw, stripped-down. debut album.

David Lee Roth, the Jagger to Ed’s Hendrix, was never a great singer, but he was one of rock's greatest showmen. Undoubtedly, Van Halen wouldn't have made it so big without DLR's charm, athleticism and shtick. At the time, I was torn between Roth and Hagar - you had to pick a side in 1986 - but I'm firmly in the Roth camp now and appreciate his musicality more than ever: the turbo-charged cover of John Brim's 'Ice Cream Man' and the 'shooby doo wop' break down of 'I'm The One' on this record clearly have Dave's DNA running through them. Roth's love of soul, R&B, and, yes, jazz made Van Halen a unique rock band, and I’m sure, set me off down many musical paths in the same way that Ed's playing did.

(2) '3' - Led Zeppelin (1970)

For a year or two, I was more than content to listen, almost exclusively, to the Van Halen catalogue and related albums (the first Montrose album, ‘Eat em & Smile’ etc.). Around that time, I bought, and wore out, a VHS of Van Halen’s ‘Live Without a Net’, expensively procured from The States via Shades Records. The concert closed with a cover of Led Zep’s ‘Rock n Roll’ which pointed the way forward. In some ways, it was a very logical step: Van Halen were America’s premier heavy rock band; Led Zep were Britain’s (apologies to fans of Aerosmith and Deep Purple). I remember borrowing a cassette copy of ‘Four Symbols’ with ‘In Through the Out Door’ on the flp side from a mate's older brother. He’d drawn the four symbols themselves on the tape spine too, if memory serves. Pretty cool. (This early exposure might also explain my appreciation for LZ’s often unfavoured last album).

As with Van Halen, I quickly devoured the Zeppelin catalogue – and what a catalogue! Choosing a favourite of the first six is hard, but the third stood out for me. Like Van Halen, Zeppelin were very diverse for a heavy rock band, balancing crunching riffs against acoustic delicacy. On the third album, the balance was more heavily tilted towards the acoustic stuff – like ‘That’s The Way’ and ‘Tangerine’.

It was also, I think, the first time they’d shown the Eastern influence in their music (on ’Friends’) which became more apparent in Kashmir and other later classics. Of course, Zep were a product of that late 60s British blues boom, and they’d already appropriated the work of many old blues singers by this time, but this album’s ‘Since I’ve Been Loving You’ is surely their best outright blues song.

This was one of those albums where every single track was my favourite at one point in time. Apart from the throwaway closer ‘Hats off to (Roy) Harper’. Sorry, Roy.

Years later, I wrote the Andy’s Records recommendation for this and it always sold disproportionately well – I’d like to think my strapline had something to do with: “For those who would dismiss Zeppelin merely as the progenitors of heavy rock, this is the album to convince otherwise.” You need to say it in a Tommy Vance voice. For me, it was definitely a gateway from heavy rock into folkier music. I also had a huge amount of fun tracking down Led Zep related albums: Plant’s varied solo career, The Yardbirds, The Honeydrippers, PJ Proby, The Firm, even the Death Wish 2 soundtrack. Not all of it was good, but I did discover the brilliant Terry Reid this way, and finding an original copy of Terry Reid’s ‘The River’ in World Records in 1990 remains my single-most exciting crate-digging moment. And given that this is supposed to be about posting album covers, can we have a moment to appreciate the brilliantly bonkers rotating ‘volvelle’ sleeve. Amazing.

(3) ‘The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan’ – Bob Dylan (1963)

Once you start listening to acoustic music, you sort of have to listen to Dylan, right?

I remember my mum, a big music fan, having three 7 inches that particularly grabbed my attention as a child: Elvis Presley’s ‘Kid Galahad’ ep (boxing and Elvis – what’s not to love?); The Beatles ‘Twist & Shout’ ep; and Bob Dylan’s ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ ep. Sadly, of the three, the Elvis is the only one I still have. My brother and I played the hell out of the Dylan one, probably wrecking it in the process.

So, it was probably inevitable that ‘Freewheelin’ was the first Dylan LP I heard. It was a good starting point. ‘Blowin' in the wind’, ‘Masters of War’ and ‘Hard Rain’ appealed to my increasing earnestness as a young man – it was probably the first time I’d listened to songs with a serious message. The more delicate moments resonate with me now – ‘Corrina, Corrina’, ‘Don’t Think Twice…’ & the gorgeous ‘Girl from the North Country’ (one of my favourite songs by anyone).

Both my brother and I excitedly explored other Dylan albums, him probably more so than me, helped in no small part by our uncle - big folkie and record collector. One day, I remember him saying to me, “If you like Dylan, see what you make of this…” He handed me his headphones which proceeded to blast out the opening bars of ‘Erin-go-Bragh’ from Dick Gaughan’s ‘Handful of Earth’. I was hooked immediately. Gaughan became a hero to me and remains the artist I’ve seen in concert the most times (I picked ‘Handful of Earth’ on my previous ‘10 influential albums’ list last year in case you’re wondering). From there, I definitely had a folk phase: Sandy Denny, Fairport, Watersons etc. but mostly Gaughan. This coincided with me starting working at Andy’s Records in ’95 under a manager whose folk knowledge surpassed even that of my uncle's.

By this time, if I was listening to Dylan at all, it was his 70s work (‘Blood on the Tracks’, ‘Desire’) rather than the early folkier stuff (Judas!) but ‘Freewheelin’ had cast a powerful spell. There was something about the cover too that fired my imagination, and still does: a young couple rushing through a snow-covered Greenwich village, her clinging so close they’re almost one person. It seems somehow to encapsulate the idealism of young love (and perhaps the era itself): the excitement, the helpless intoxication, the hope.

(4) ‘Blue’ – Joni Mitchell (1971)

Let’s put it right out there: Joni Mitchell’s ‘Hejira’ is my favourite album by anyone. Of course, ‘Hejira’ wasn’t the first album of Joni’s that I heard; I’d be amazed if anyone ‘got into’ Joni by hearing ‘Hejira’ first - it’s an album that you need to live with (and also, I dare say, have some life experience to fully appreciate).

Bizarrely, I became aware of Joni through my love of Led Zeppelin. I remember reading an interview with Robert Plant where he admitted to have been star struck when he met Joni Mitchell. (You can hear the Joni influence in Led Zep IV’s ‘Going to California’ now I think about it). I didn’t know anything else about her, but Plant’s approval was enough.

I have a very clear memory of buying ‘Blue’ in Archer Records on Leicester’s Highcross Street (Summer 1990, I think). Archer Records was a great little shop – the kind that maximised every square foot: tape racks completely filled one wall; vinyl browsers that surrounded the counter (you had to hand your money over the racks); aisles so narrow you always had to excuse yourself whenever you moved. There was so little room in the shop the CDs weren’t even on display at that time – you had to ask to the owner (Pete, I think) to look through his CD folder! As a very inexperienced crate-digger, I remember being quite intimidated in there, not because he was unfriendly but the rest of the clientele tended to be old geezers who knew their stuff and I was just a long-haired youthful interloper who felt out of his depth. Because of this, I wasn’t comfortable browsing for any length of time – there was a sense of feeling ‘eyes on me’, particularly as the ‘M’ section was right next to the counter. I didn’t have time to make a considered purchase – I just grabbed the one with the cover that appealed most. And that was the one with Tim Considine’s stark, blue-tinted, photo of Joni at the microphone.

From the opening bars of ‘All I Want’, I was hooked. “I am on a lonely road and I am traveling, looking for something, what can it be?” seemed to speak to my adolescent angst in a very personal way. It perhaps also spoke of her own musical restlessness and the journey that she was about to embark on. Each album that followed took her further away from the Laurel Canyon folkie that she’s sometimes mistakenly pigeon-holed as. Her run of albums in the 70s is as good, and 'progressive', as any body of work in ‘pop’ music. Just thinking about the musicians she played with in that time will give you an indication of where she was headed: CSN, James Taylor, Tom Scott, Larry Carlton, Jaco Pastorious, Wayne Shorter, Charles Mingus (!) And, of course, as a listener, I was soon following in her wake, exploring the rest of that whole Laurel Canyon set, and tentatively dipping my toes further into jazz.

‘Blue’ was one of those albums where, at some point, every track was ‘my favourite’ – the one I kept returning the needle to, to play over and over. I guess what made ‘Blue’ stand out from other singer-songwriter stuff of the time was its confessional quality, its emotional honesty; you felt like you knew her through these songs: whether it was her devotion to Graham Nash and their shared domestic bliss in ‘My Old Man’ or the heartbreak of giving up her child chronicled in ‘Little Green’ – “Child with a child pretending… Little Green, have a happy ending.”

The pain of the latter was a recurring thread through her songs. I was listening to ‘Chinese Café/Unchained Melody’ on 1982’s otherwise unremarkable ‘Wild Things Run Fast’ the other day (perhaps the first album where she faltered). Not for the first time, I found myself moved to tears by the deep sorrow with which she sings, ‘My child’s a stranger: I bore her… but I could not raise her...” Even though I know Joni and ‘Little Green’ got their happy ending some years later, that line gets me every time.

(5) ‘Boy Child: the best of 1967-70’ – Scott Walker

My interest in Scott Walker began in July 1990. I can be very specific about this as it coincided with the launch of a new music magazine, ‘Select’, which happened to come with a free cassette (!)

On the tape, alongside the likes of The House of Love and James, was The Walker Brothers’ ‘My Ship Is Coming In.’ I was instantly hooked: the doom-laden baritone, Ivor Raymonde’s (father of Cocteau Twin, Simon) sweeping orchestration, the unashamed romanticism of the lyrics…

A few months later, I bought my first CD player and, on the same day, my first CD: ‘Boy Child’. It’s easy to be snobby about compilations, but this was a great introduction to Scott’s early solo work (Scott 1-4 and ‘Til The Band Comes In’). As it focuses on self-penned songs, there’s none of his wonderful Jacques Brel covers but the Brel influence is apparent in ‘The Girls from The Streets’, ‘The Bridge’, ‘Big Louise’ etc. Fantastic stuff.

Those first four solo albums were the soundtrack to my 20s. The references to Brel, Camus and Bergman sent me off exploring all sorts of European literature, film, and music, all of which shaped my identity as a pretentious twentysomething. I can’t deny Scott’s image appealed too – the former teen idol who deliberately turned his back on fame. In the summer of 1966, The Walker Brothers were as big as the Beatles. That same year Scott retired to a monastery, Quarr Abbey, on The Isle of Wight in order to study Gregorian Chant (only to have to cut his stay short after being tracked down by screaming fans). If you look carefully, he’s wearing the key to Quarr Abbey the monks bequeathed to him on ‘Boy Child’s’ cover, symbolising an ‘open door’ offer of return.

‘Boy Child’s’ fabulous sleeve notes by uber-Scott fan, Marc Almond, also fired my imagination and contributed to the Walker legend. As he put it, Scott was more Jean Paul Satre than John, Paul, George and Ringo. (The 2000 reissue of ‘Boy Child’ inexplicably replaced Almond’s sleeve notes with scribbling by the pound shop Scott Walker, Neil Hannon).

I was still very much under Scott’s spell by the time ‘Tilt’ was released in 1995 and that too was a gateway for me, a door to more challenging music.

Scott’s death in 2019 came as shock to everyone, as did the fact that the former ‘teen idol’ was 76. Despite possessing a voice seemingly weighed down by the sorrow of a thousand life-times, there was something eternally youthful about him - the boy child.

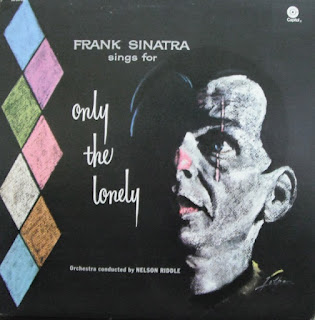

(6) ‘(Frank Sinatra Sings for) Only the Lonely’ Frank Sinatra (1958)

I can't recall the first time I heard Sinatra. Doubtless it was one of those ‘chest-out’, barnstorming anthems of his later years: 'My Way' or '(Theme from) New York, New York' perhaps. If there was one an initial impression, it was one of incomprehension, of bewilderment: Why is he singing that way? Why does he sound like he's just speaking the words?

There was no moment of epiphany for me, no ‘Road to Damascus’ type conversion. It was a gradual awakening, a kind of growing awareness. The religious analogy is not entirely inappropriate as there is a sense in which my life-changed, post-Sinatra. 'Getting' Sinatra was like arriving at an alternative world-view, a fundamental truth even - like suddenly realising the world was round (alright, spherical), that Santa Claus was just my dad dressed up and that Bon Jovi were actually never very good. I found it hard to listen to anything else after this Damascene conversion - everything else sounded insubstantial and insignificant in comparison. So, for quite some time, I listened to nothing else. When I say 'I' listened to nothing else I also mean the staff and customers of a record shop I managed at the time. Apologies for that to all concerned.

Anyway, this album comes smack band in the middle of his recordings for Capitol records, which, I think, make up the greatest body of music in popular music, and ‘…Only the Lonely’ is probably the greatest among those albums. Frank understood the importance of contrast, of light and shade: lifting them up and bringing them down. For all of his swagger, he was willing to bare his soul. And he never did it in a more direct way than on this album. These may have been ‘Songs for Only the Lonely’, as the album’s full title promises, but they are certainly not for the faint of heart. Easy listening it aint.

(7) ‘Sounds of the New West’ – Various Artists (1998)

The free CD given away with issue 16 of Uncut, entitled Sounds of the New West, might well be the best ‘alt. country’ collection on disc to this day: The Flying Burrito Brothers, Emmylou Harris, Will Oldham, Calexico, Lambchop, The Handsome Family, Neal Casal, The Pernice Brothers, Josh Rouse...

I was already into a lot of this music without realising there was a genre as such: a friend had lent me a copy of The Jayhawks' ‘Sound of Lies’ and my favourite album of ’96 was Palace Music’s 'Arise Therefore' (Will Oldham at his most bleak). But this compilation seemed to crystallise ‘the movement’ in the UK and set Uncut up as standard bearer for this kind of music.

There was something wonderfully cool about being part of an underground scene in those early days. I distinctly recall our excitement at being able to fill a whole shelf of these obscure artists at Andy’s Records (although it was tempered by having to file them at the bottom of the country section after the compilations and line dance CDs...)

Leicester seemed like the unofficial capital of the U.K's alt country scene at the time. Thanks largely to Ian from Magic Teapot's promotions, artists like The Handsome Family, Lambchop, Chris Mills, Neal Casal, Grand Drive etc played regularly at the Princess Charlotte and the grandly named International Arts Centre (which was essentially a bingo hall – a solo Kurt Wagner playing to about 20 people there remains one of my all-time favourite gigs). Ditto Cosmic American Music and the Maze in Nottingham. These were exciting times for me: from sharing beers and discussing a mutual love of the Louvin Brothers with Brett Sparks of The Handsome Family, to deeply insulting one of my all-time heroes Mark Olson (ex-of The Jayhawks)...

Me: "Your new album (Political Manifest) seems like a bit of a change in direction...it's more political"

Mark: "We've always been political."

Me: "Ok... musically, it's a bit of change too - it's less acoustic more... funky."

Mark: "We've always been funky."

And so it went on... and so my aspirations towards a career in music journalism ended

(8) ‘If Only I Could Fly’ – Merle Haggard (2000)

Ok, here goes. I know it's not cool to say this but... I love country music. Real country music, that is. It almost certainly goes back to my childhood. My mum was a huge fan at a time when country was probably at its most unfashionable. Distinctly, I recall the strains of Tammy Wynette's D.I.V.O.R.C.E echoing through our house (prefiguring her own actual D.I.V.O.R.C.E from my dad).

The whole ‘alt country’ scene sent me digging back further for ‘gold in them there hills’ where I rediscovered songs I’d half-forgotten from childhood. Still in the middle of my Sinatra obsession, my preference was for country crooners - guys that could really hold a tune: Faron Young, George Jones, Ray Price, Johnny Paycheck and Merle Haggard.

The 20-year-old Merle Haggard was famously an inmate at Cash's first San Quentin prison concert in 1958 and he often credited this as the turning point in his life. The young Hag made much of his outlaw credentials: I'm A Lonesome Fugitive, Branded Man, Mama Tried etc.

‘If Only I Could Fly’ came out around the same time as Johnny Cash’s celebrated American Recordings series for Def Jam and they are a good comparison (although I think this is a far superior album to any of them). His once beautiful voice is rather grizzled, and, lyrically, this is an old man (63), not quite growing old gracefully: “Watching while some old friends do a line, holding back the want in my own addicted mind,” are the opening lines of the album. There are moments of real tenderness too, mostly directed to his fifth wife Theresa: ‘Turn to Me’ and ‘Proud to be your old man’ (“I might be over the hill but you make growing old quite a thrill…”). Admitting his past to his new, young family is another heartfelt theme (“I knew someday you’d find out about San Quentin…”). There’s a delightful paean to their domestic bliss in the form of ‘Leaving’s Getter Harder All The Time’ (“If I don't travel, I don’t make a dime and leaving's getting harder all the time. That old fishing pole looks better every day…”) Perhaps best of all is the beautiful title track, a cover of the Blaze Foley song (the only cover on the album) – a song about enforced separation and a song for these strange times if ever there was one.

(9) ‘The Black Saint & The Sinner Lady’ Charles Mingus (1963)

By about ’91 or ’92, with Cook and Morton’s Penguin Guide to Jazz as my bible, I’d worked my way through Goldsmith’s music library’s jazz catalogue. I’d also worked out my limits: I’d learnt to steer clear of anything too ‘modern’ after hitting a brick wall with Coltrane’s ‘Ascension’.

This album was a watershed for me in appreciating more difficult jazz. I already owned his collaboration with Joni (and was well aware of his status as an outsider figure), but this was definitely a beginning of sorts. It had beguiled me for a long time: the evocative album title (was he ‘The Black Saint’?); the curious Cossack-hatted figure on the cover smoking a pipe; the biblical proclamations in the songs' subtitles (Stop! Look! And Listen, Sinner Jim Whitney!).

Supposedly conceived as a six-part ballet (!), Mingus himself described it as ‘ethnic folk-dance music’. It’s an incredibly dense but varied piece of work: growling horns rise and swell into a glorious hypnotic cacophony before dissipating into flamenco guitars.

For me, there’s something about it that conjures up the sounds and urban sprawl of a big city – screaming police sirens, the subway rattling underfoot, steam pouring out of the pavements…

As Richard Williams put it in the foreword to Mingus’ brilliantly bonkers autobiography ‘Beneath the Underdog’: “Never was there music in which violence and tenderness were so thoroughly entwined as that of Charles Mingus.”

(10) ‘ Suite for Sampler ECM Selected Signs 2- Various Artists (2000)

Having spent the last five years almost exclusively collecting music on the ECM record label, this had to be my final choice.

For a long time, even as a hardened jazzer, the idea of European jazz was a little off-putting: jazz was African-American music, the joyful sound of New Orleans, the sound of oppressed rising above injustice for a few glorious minutes – Oh, play that thing!

In comparison, everything on ECM (Edition of Contemporary Music) seemed cold, cerebral and, most importantly as a poorly paid record store manager, EXPENSIVE. I could get three mid-price Columbia Jazz masterpieces for the price of one ECM. So, when a £5 ECM sampler appeared as a new release one Friday at Andy’s Records 20 years ago, I was willing to put aside my preconceived ideas.

As any sampler should be, it’s quite representative of the label’s output - but in no way could this be considered an easy introduction. Gianluigi Trovesi’s opening ‘In Cerca di Cibo’ is a mournful duet between clarinet and accordion – beautiful but not exactly a standard opener. The tone veers off widely with Nils Petter Molvær techno-infused jazzy D&B. Elsewhere, there are selections from Heiner Goebbel’s dense ‘Surrogate Cities’ which, in the words of the label, is ‘concerned with the dynamic power and the power dynamics of the modern city - it is an examination of the 'concrete jungle' in all its complexity, complete with musical-historical flashbacks’. It also seems to evoke that defining moment of the twentieth century: the holocaust.

My personal gateway among this diverse selection was Bobo Stenson’s brilliant ‘Polksa of Despair’, which somehow seemed to combine a European sensibility AND a swinging rhythm.

My interest in ECM coincided with an interest in European cinema and there are connections between the two. Even if you have no interest in jazz or contemporary classical music, Manfred Eicher’s status as ECM’s ‘auteur’ is remarkable. Since founding the label in 1969, as well as producing almost all of the label’s recordings himself, he has almost single-handedly overseen the label’s distinctive aesthetic and sound – in his words, ‘the most beautiful sound next to silence.’